Introduction to Women’s Historical Gift of Love: the Evolution of Empathy

Many of us here know the pain of being hurt by women — through betrayal, false accusation, alienation, or cruelty. For those who have lived that, it can be hard to read praise of the feminine without flinching. That’s natural.

Yet healing often begins when we can hold two truths at once: some women have done harm, and women as a whole have also given civilization gifts. In this essay David Shackleton looks at women’s impact on empathy. Shackleton explores how, across generations, mothers quietly expanded humanity’s moral depth while men advanced knowledge and invention. Both streams were essential to our progress, and both were not mutually exclusive.

Feminists have long tried to obscure this moral achievement because it doesn’t fit their preferred path for women — getting a job. They celebrate women who break ceilings but ignore those who built the foundations of love and empathy that made civilization humane. The following is an excerpt from David Shackleton’s forthcoming book, Matrisensus: The Masculine Collapse and Feminine Shadow. See what you think. How have we ruined this balance and to what effect? Tom Golden

Women’s Historical Gift of Love: the Evolution of Empathy

Civilization has been built by two parallel and complementary streams of human achievement. On one side, while most men did not add to the collection of human knowledge, a few exceptional men pushed forward the frontiers of knowledge: explorers charting unknown lands, scientists discovering natural laws, philosophers clarifying moral principles. On the other side, while most women made no difference in their parenting from the way they had been treated in their own childhoods, a few exceptional women advanced the frontier of love – especially empathy – in the private realm of the family, transmitting new ways of caring for children that slowly reshaped society. Both gifts were indispensable.

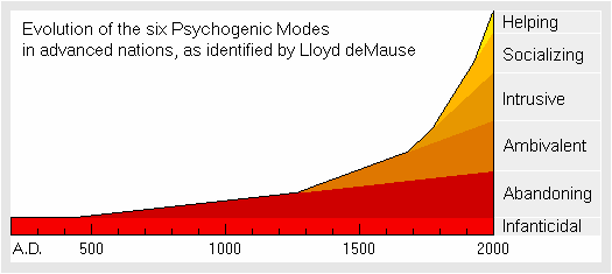

The historian of childhood Lloyd deMause argued that the deepest motor of history is not politics or economics, but the way parents treat their children. Most parents, he observed, simply repeat what they themselves experienced. Yet in every generation, a few mothers break the cycle, heroically choosing to treat their children with greater tenderness and empathy than they had received. Since mothers in subsequent generations then repeat these new patterns, these quiet decisions accumulate across generations, slowly elevating culture.

To give shape to this process, deMause described six successive childrearing modes, each producing characteristic personality structures and cultural patterns:

Childrearing Mode – Description – Psychological Outcome

Infanticidal: Routine killing or abandonment of unwanted infants → Schizoid, fragmented personalities

Abandoning: Physical survival ensured, but emotional neglect and use of wet nurses or servants → Masochistic, dependent personalities

Ambivalent: Parents swing between affection and cruelty, discipline by fear → Borderline, unstable personalities

Intrusive: Parents invade the child’s inner life, controlling thoughts and feelings → Depressive, guilt-ridden personalities

Socializing: Parents train children to conform to external norms and roles → Neurotic, rule-bound personalities

Helping: Parents empathize with children’s needs and support growth toward autonomy → Individuated, creative personalities

(If you find yourself doubting the historical advance of empathy or that childrearing was so brutal in the past, consider that it is less than 500 years since we burned people alive at the stake in public executions. How much less empathy must people have had at that time in order to watch and approve of such horrific spectacles?)

deMause explained:

“Psychogenesis is not a very robust process in caretakers. Most of the time, parents simply re-inflict upon their children what had been done to them in their own childhood. The production of developmental variations can occur only in the silent, mostly unrecorded decisions by parents to go beyond the traumas they themselves endured. It happens each time a mother decides not to use her child as an erotic object, not to tie it up so long in swaddling bands, not to hit it when it cries. It happens each time a mother encourages her child’s explorations and independence, each time she overcomes her own despair and neediness and gives her child a bit more of the love and empathy she herself didn’t get. These private moments are rarely recorded for historians, and social scientists have completely overlooked their role in the production of cultural variation, yet they are nonetheless the ultimate sources of the evolution of the psyche and culture.”

And again, in conclusion:

“Because childrearing evolution determines the evolution of the psyche and society, the causal arrows of all other social theories are reversed by the psychogenic theory. Rather than personal and family life being seen as dragged along in the wake of social, cultural, technological and economic change, society is instead viewed as the outcome of evolutionary changes that first occur in the psyche. Because the structure of the psyche changes from generation to generation within the narrow funnel of childhood, childrearing practices are not just one item in a list of cultural traits—they are the very condition for the transmission and further development of all other cultural elements, placing limits on what can be achieved in all other social areas. … Childhood must therefore always first evolve before major social, cultural and economic innovation can occur.”

To summarize, deMause outlined a new, psychogenic theory of history: that cultural evolution is driven overwhelmingly by the nature of childraising, and that this is dominated by mothers, with those few mothers who courageously advance their own psychic maturity so that they are able to love their children better than they themselves were loved as a child being the engine of advancing social empathy and thus of general cultural progress. Far from being powerless and oppressed figures in history, this theory places women at the centre of cultural evolution, the prime cause. Women provided the substrate, the progressively advancing psychological and cultural backdrop, and men innovated the physical techniques and technologies that delivered greater health, longer lives, better living standards, and increased freedom. It was truly an equal partnership.

A few examples illustrate women’s contribution:

The Breastfeeding Revolution: In eighteenth-century England and France, mothers began to nurse their own children instead of sending them to wet nurses. This seemingly small change radically increased infant survival, deepened maternal bonds, and helped prepare a generation with greater capacity for empathy. Rousseau’s Émile (1762) gave voice to this cultural shift, insisting that “the mother’s milk is the milk of virtue.” Within a century, England and France were leading the world in science, democracy, and industrialization.

Abolitionism: While men like Wilberforce led parliamentary campaigns, the conscience of the abolition movement was profoundly maternal. Writers such as Elizabeth Heyrick, who called for immediate abolition in 1824, and Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) moved millions, exemplified how women’s empathy translated into moral revolution. Abraham Lincoln’s (perhaps apocryphal) remark on meeting Stowe — “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war” — captures this dynamic.

The Rise of Universal Human Rights: The very notion that all people possess inherent dignity and equal rights, regardless of class, race, or sex, emerged alongside the expansion of empathy across generations. While men codified these rights in declarations and constitutions, women’s work of nurturing developed the human capacity to imagine others as equally valuable. The family was the first school of equality: the mother who held her child in love transmitted, in seed form, the conviction that every human being deserved care and respect. As historian Lynn Hunt argues in Inventing Human Rights (2007), the eighteenth century saw the growth of “empathetic imagination” through novels, letters, and family life, and this undergirded the spread of rights discourse. Without this interior revolution of feeling, the abstract principle of rights would have rung hollow. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen (1789) and later the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) were thus the public crystallization of a private moral revolution that mothers advanced in the nursery.

Child Labor Reforms: In nineteenth-century Britain and America, mothers and women’s societies were prominent advocates for laws restricting child labor, pressing legislators with the moral claim that children were not merely economic assets but human beings with rights and dignity.

Nursing and Care: Florence Nightingale’s transformation of nursing in the Crimean War and afterward reframed medicine as compassionate service, professionalizing an ethic of care. Her Notes on Nursing (1859) became foundational for modern healthcare.

Education and Literacy: Across the West, women were the primary transmitters of literacy and moral instruction in the home. In the nineteenth century, they became the backbone of the teaching profession, extending their empathic role into the public sphere.

Each of these steps paralleled breakthroughs in men’s domain: Newton’s Principia (1687) reshaping science, Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859) transforming biology, explorers charting the globe, inventors powering industry, philosophers clarifying the principles of liberty and democracy. Men advanced the frontier of truth; women advanced the frontier of love.

The prevailing feminist narrative has been that women were excluded from history’s great achievements and silenced by male domination. But deMause’s research reveals a deeper truth: women were not absent from progress; they were its other half. Their contributions were less visible only because they took place in private rather than public realms.

That this polarized narrative of victim and oppressor was completely mistaken is now clear:

Men’s gift of truth expanded humanity’s knowledge and control over the world.

Women’s gift of love expanded humanity’s moral and emotional capacity.

This is perfect archetypal balance. Women’s gift was as important as men’s. Both were necessary, both indispensable. Civilization depends equally on both.

Seen in this light, the family hearth was as revolutionary as the laboratory. The quiet choices of mothers: to hold rather than strike, to nurse rather than abandon, to soothe rather than shame, carried forward across generations until they reshaped entire cultures. Just as Galileo pointed his telescope toward the heavens, so did mothers across centuries point their empathy into the hearts of their children, and the world changed.

History must honor both gifts: truth and love, discovery and empathy, masculine and feminine. To overlook either is to tell only half of the human story. We have been doing that for too long. It is time that we stopped.

References

Lloyd deMause, The Emotional Life of Nations, Karnac Books, New York, 2002, p.110

Lloyd deMause, The History of Childhood, Harper & Row, New York, 1974, p.12

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Émile, or On Education (1762), Book I. Modern edition: trans. Allan Bloom, Emile: or On Education, Basic Books, New York, 1979, p.44

Attributed remark by Abraham Lincoln to Harriet Beecher Stowe, 1862, during her White House visit. Source uncertain; first recorded by Annie Fields in Life and Letters of Harriet Beecher Stowe (Houghton, Mifflin, Boston, 1897), p.133.

Lynn Hunt, Inventing Human Rights: A History, W. W. Norton, New York, 2007

Florence Nightingale, Notes on Nursing: What It Is and What It Is Not, Harrison, London, 1859

Isaac Newton, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, London, 1687

Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, John Murray, London, 1859