(written in 2010) This is the final post in this series examining how science has been bent to serve a false narrative. According to ResearchGate, this particular article has been cited 299 times — placing it among the most frequently referenced works of its kind. In other words, it has helped spread a great deal of misleading propaganda about men under the guise of research. Keep that in mind as you read how it was constructed.

_________________________________________

Changing the Norms to fit the Narrative: CMNI

The last study we will examine in this series will be the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory (CMNI). (Development of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory published in Psychology of Men & Masculinity, Vol 4(1), Jan 2003, 3-25.)7

This inventory purports to measure the conformity or lack of conformity to what it considers the masculine norms for this culture.

The first problem I see in this inventory is that the norms they have chosen as being masculine norms don’t seem like norms at all. Here’s a list of what this inventory considers masculine norms:

Power Over Women

Violence

Disdain for Homosexuals

Playboy

Winning

Emotional Control

Risk-Taking

Self-Reliance

Primacy of Work

Pursuit of Status

Dominance

It’s the first four that I find most off target, Power over Women, Violence, Disdain for Homosexuals, and Playboy. I just can’t see them as masculine norms for our culture. These four actually seem more like negative stereotypes which is hardly the sort of thing that will be effective in a professional inventory. My initial reaction was to think this inventory is painting masculinity in a very poor light. These “norms” are clearly negatively charged and not what one would expect. Why would any inventory choose such negatively charged words? Are they claiming these are generic masculine norms? The study clearly states that it is studying the reaction to the masculine norms of the dominant culture of the US. It says:

The inventory was constructed to assess the extent that an individual male conforms or does not conform to the actions, thoughts, and feelings that reflect masculinity norms in the dominant culture in US society. (page 5 Development of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory)

This sounds very much like they are examining generic norms. The article also states:

Gender norms also operate when people observe what most men or women do in social situations, are told what is acceptable or unacceptable behavior for men or women, and observe how popular men or women act (page 3, Development of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory).

So they are claiming that violence, power over women, disdain for homosexuals and being a playboy are all norms in the US and men are encouraged to act out these behaviors? That seems to be a very outlandish claim given that the norms for men are usually based on the ideas of provide and protect. Many normative messages received by males include things like “never hit a girl” or some other imperative that says the opposite to what this inventory is claiming are cultural masculine norms.

The CMNI is not claiming to study some arcane aspect to masculine norms but instead is stating they are interested in the basic masculine norms as described above. That is pretty straight forward but the researcher throws in another twist and claims that the norms the inventory wants to study are only the norms of white heterosexual middle and upper class males. The reasoning, according to this researcher, is that these white males are the “dominant” group and other males would be affected by this dominant group. So this inventory is not just about male norms for the United States, it is specifically about white heterosexual middle and upper class male norms. Here’s the explanation from the article:

“The construct was chosen because Mahalik (the researcher) posited the gender role norms from the most dominant or powerful group in a society affect the experiences of persons in that group, as well as persons in all other groups. Thus, the expectations of masculinity as constructed by Caucasian, middle- and upper-class heterosexuals should affect members of that group and every other male in U.S. society who is held up to those standards and experiences acceptance or rejection from the majority, in part, based on adherence to the powerful group’s masculinity norms.” (page 5-6 Development of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory)

This inventory seems to assume that white heterosexual male middle class norms impact the rest of men in our culture. This seems a bit off to me when you look at the sorts of things that young men are looking up to and emulating. It seems to me that hip hop, word choices, language styles, and dress styles, and behaviors of black males are having a greater impact on young men then stuffy middle class and upper class whites. Furthermore, aren’t the rates of violent crimes much higher for blacks than whites? Aren’t the violent crime rates for lower socioeconomic groups much higher than the middle and upper class? If this is correct why are they ascribing violence as a prominent norms for middle and upper class white males? It doesn’t add up.

So this inventory clearly states that it is not attempting to gauge the norms of all men, it is looking to isolate the norms of a very specific group, the white heterosexual middle and upper class males of the US and then labels them in a very negative fashion. This is beginning to remind me of the way white males are isolated on TV as being recipients of bashing and shaming and sidesteps the problem of voicing any sort of negative comments about women, gays, blacks or other minority males.

Let’s have a look at the four categories that seem most ill placed in this inventory.

1. Violence

Is violence a masculine norm? I don’t think so. In 2008 99.82% of men in the United States were not arrested for a violent crime. That leaves about .18% who were. Very far from being a norm. Of the men you know how many are violent? How about your father, brother, nephews or other male relatives, are they violent? Probably not. And if they were, do you look up to their violent behavior? Do they model what you would like to be? Saying violence is a masculine norm in this culture shows a hateful attitude towards men and masculinity. In actuality, violence occurs when the role for men breaks down. Men’s roles have traditionally been to provide and protect. Are men sometimes violent while protecting others? Yes. But that is far from lumping all men into a norm of violence. Yes, some men can be violent, but no, violence is not a descriptor of men in general and to imply that violence is a norm for men goes beyond being anti-male and moves into being a hateful attitude toward men and masculinity.

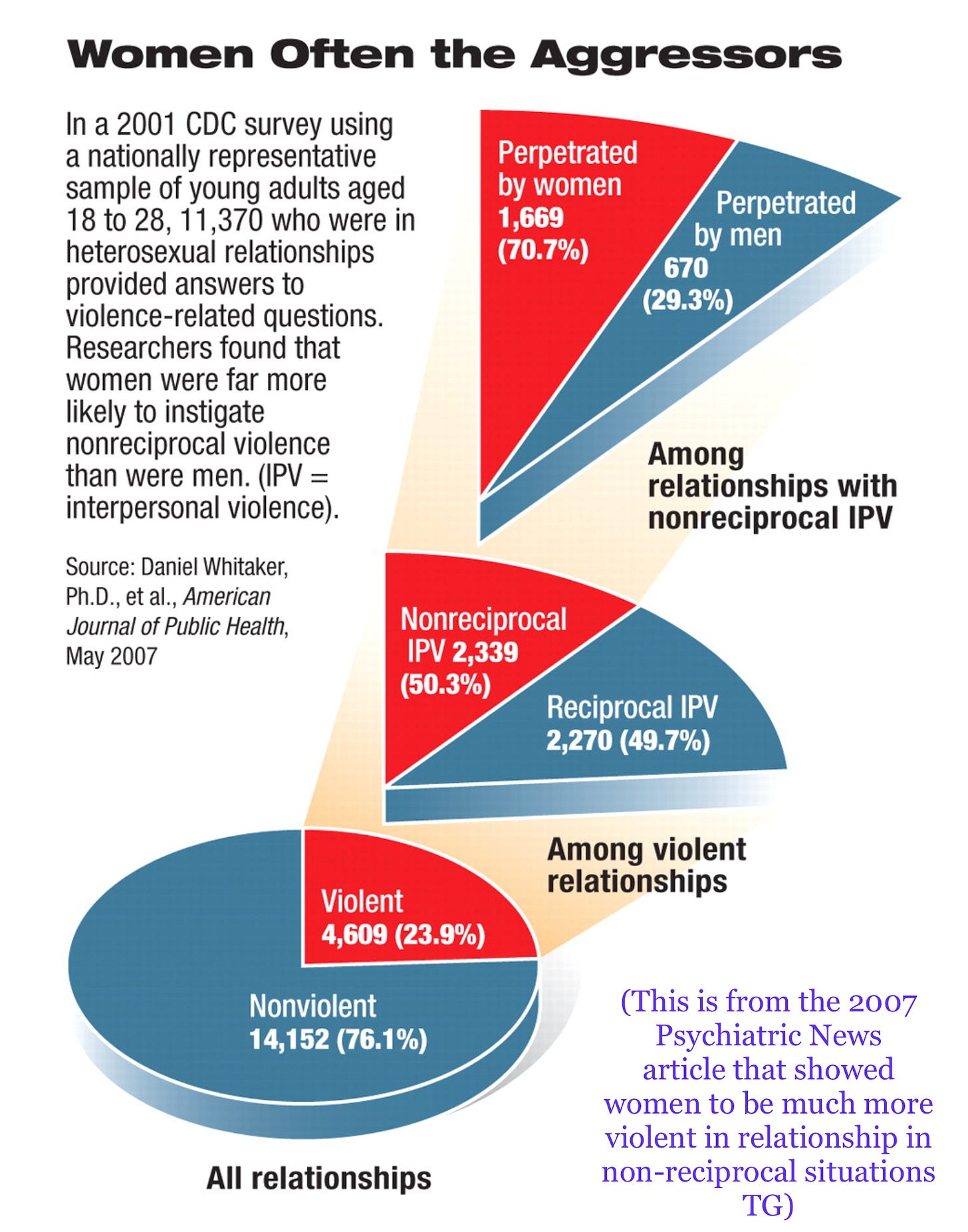

Just imagine that we are creating a scale of norms for women. We know that women commit child abuse more often than men and that women initiate violence in intimate relationships more often than men.4 Knowing this, should we add to our norm scale that women are child and spouse abusers? Or that women are violent? Of course not, and anyone who tried to do this would be laughed at. Only a small percentage of women abuse children or initiate domestic violence. In 2001 243,000 women were labelled child abusers by HHS. Out of the population at the time of about 143 million women that comes out to about .17%. That is about the same percentage abusers per capita as there were males convicted of violent crimes and yet we wouldn’t dream of saying child abuse was a norm for women would we? Of course not. So why is it that no one objects when researchers try the same thing on men and even boys? This double standard, I suggest, is a strong indicator of misandry.

Disdain for Gay People

Some men and some women surely have disdain for gay people, but is this even close to being a defining characteristic of masculinity? Again, if this were about women, the offenders would be thought of as witless. The idea that most men have disdain for homosexuals is simply nutty. Implying or outright claiming that this sort of characteristic is representative of a birth group is again misandrist.

Power over Women

The norm of power over women is as perplexing as the previous two. Where is the data showing that most men have a tendency to want power over women or that that behavior is frequent enough to consider it a norm? I could find nothing to support this. This may indeed be the case in a tiny minority not unlike the female child abusers mentioned above, but hardly the frequency to call it normative. There are likely some men who do want power over women, just like there were indeed some men who were violent, but I see no reason to believe that most men do. Making a claim that one birth group wants power over the other birth group seems to be on very shaky ground. It seems to me that this is just another way to shame and stereotype men. Again, there is no evidence to support such a claim.

Playboy

Is playboy a norm for men? It seems like the same problem with this one as with all the others. Yes, some men are interested in continuous and multiple relationships and behave in a way that would be consonant with the playboy role but is that the norm for men? I don’t think it is even close.

I wrote to the creator of this inventory, James Mahalik, and asked him about these four “norms” and the reasons for their inclusion in this inventory. He referred me to the journal article being discussed here and claimed the article might explain this for me. I went back and re-read it. I was not surprised to see that the only reference to how these norms may have appeared was a list of articles dating from 1975-1995 that Mahalik claimed were used for his search of the literature. One of those he cited was a book by I. M. Harris written in 1995 and titled “Messages Men Hear: Constructing Masculinities.”9 I found this book and discovered that “Playboy” was one of the roles the book mentioned. It was one of four roles under the category of men’s ways of loving. The other three in that category were “breadwinner, faithful husband and nurturer.” Each of those sounded complimentary as opposed to playboy which seemed more judgmental. As I went through the book I found that the book’s author stated that the playboy role was only chosen by 1% of the men surveyed as their dominant role. This leaves us with the obvious question of why would Mahalik choose playboy as a norm when the source he claims to have used to find those norms listed playboy as a very infrequent choice for men? It just didn’t add up and it looks very suspicious.

These four “norms” violence, power over women, playboy, and disdain for homosexuality seemed to pass harsh judgment on men and boys and seemed much more like stereotypes than norms. But questions arose in my mind. Was I overreacting? More specifically, had no one done this before? Was naming norms of men as being very negative new or was it a continuation of earlier research? To answer this question I pulled together examples of words that had been used as norms for men during the period of 1974 to 2003 and the CMNI. The chart below offers examples of the terms that have been used to describe masculine norms.

Notice that the norms that were used prior to 1990 seem to be neutral. Examples included competency, level headed, independence, aggressive, forceful, suppressing emotion, willing to take a stand, assertive, and self-contained. All of these could be seen as being close to neutral with some like “level headed” or “self-confident” seeming even a bit complimentary. Someone could have some of any of these qualities, like some aggressiveness, some forcefulness or some assertiveness and depending on the situation would be considered okay. Now think of having some violence. Nope, you can’t even have a little bit of that before you are judged harshly. Same thing with power over women, playboy or disdain for homosexuals. A little bit of any of those and you are sunk. These four categories from the CMNI seem quite different from all of those from 1970-1986.

The Shift in Thinking

Why would any academic psychological inventory be willing to place such negative labels on a birth group in this manner? In order to even partially answer that question we will need to momentarily divert our attention away from this inventory and take a quick look at the ideological shift that has occurred since the late 20th century in the academic psychological community.

Prior to the 1980’s the psychological community thought of sex roles in terms of traits. Men and women were seen as different but not seen in terms of one being better or worse then the other. The trait theory was in its heyday and different traits were assigned to each sex. Norms such as strong and aggressive went to the men’s column, norms such as nice and nurturing went into the women’s column. Very simple and obviously inadequate as a measure of both masculinity and femininity. After the 1980’s feminist writings started gaining influence in the academic study of men and masculinity. It’s not a big surprise that with this shift men/masculinity started being seen as “the problem.” Prior to this time men and masculinity had been seen as a group of traits, now this perception shifted and instead men and “masculinity” starts catching blame for the world’s ills. I know that is hard to believe but it is true. Feminism, which had found men to blame through “patriarchy” for many of women’s problems now was beginning to become dominant in the discourse about men and masculinity. One of the influential writers in the late 20th century was feminist R W Connell. It was in the mid 1980’s that Connell began writing about “hegemonic” masculinity. Connell’s book on Masculinities and specifically hegemonic masculinity came out in 1995 and was considered a top resource by academic psychologists on the study of masculinities. Since that time these ideas about hegemonic masculinity have become entrenched into academic psychology. But just what does Connell mean by hegemonic masculinity? According to an article in the Journal of Clinical Psychology in 2005 Connell defines hegemonic masculinity as “the dominant notion of masculinity in a particular context which serves as a standard upon which the “real man” is defined. Connell claims it is built on two legs, one being the domination of women and the other the hierarchy of intermale dominance. It is also shaped to a lesser extent by the stigmatization of homosexuality.”

Now in the academic psychology world masculinity through its perceived domination is seen as THE problem. We have gone from an overly simplistic trait view to an even more overly simplistic view of masculinity as being bad, as being responsible, as being the problem. It is amazing to me that so many educated people can take such a misandrist viewpoint. Masculinity is obviously very complex, there are multiple models pushing multiple norms, some violent, some peaceful, some yin and some yang. “Never hit a girl” or “girls first” were surely messages that most boys received loud and clear. But they were among many. It is very complex and to try and boil it down to men being bad seems incredibly simple minded. So many different voices it is preposterous to claim that only one very negative voice defines the masculinity that all other males will follow.

It is worthwhile noting that R W Connell changed sexes from male to female in 2006. He was Robert W Connell and then became Raewyn W Connell. I have heard that Connell went to a professional conference after this change and presented a paper as a woman, Raewyn Connell, without giving any sort of notification to many of his peers of his profound change. I understand there were more than a few dropped jaws at the professional meeting. Yes, what many academic psychologists believe about masculinity was drawn directly from the writing of someone who at best had an ambivalent perception of what it is to be a male. Someone who decided to cease being male. Hard to see this viewpoint as anything near fair and balanced.

Apparently academic psychologists in the U.S. have taken Connell’s theories of hegemonic masculinity and siphoned out the negative traits and distilled it down to what they now call “Toxic Masculinity” which is characterized by: ruthless competition, violent domination, inability to express emotions other than anger, unwillingness to admit weakness or dependency, devaluation of women and all feminine attributes in men, and homophobia.

It should be getting more clear about the origin of those four categories of the CMNI. (Violence, Power over women, Disdain for Homosexuality and Playboy) They are the basis to the ideas of hegemonic and/or toxic masculinity. It seems that Mahalik must have liked the idea of hegemonic masculinity and toxic masculinity and liked them so much that he just inserted those into his inventory as norms not because there was any research that backed up those choices, but because they were the foundation of the latest and hottest theory among his peers.

I can personally testify that the ideas of toxic masculinity are alive and well in the American Psychological Association’s one place to study men and masculinity, APA’s Division 51. It’s a hotbed of feminism and attachment to the ideas of toxic masculinity. I was on the mailing list for this group for some time (until I was unceremoniously tossed out) and was continually shocked at the adherence to these ideas. The basic unvarnished theory is that masculinity is the source of our problems and that men need to learn to be more mature which is “code” for men need to act more like women. One of the list members actually wrote a message where he stated just that. Men needed to be more mature like women and the world would immediately improve! This is the primitive feminist lens through which they see the world. They don’t even seem the least bit aware of the ideas and psychological theories around mature masculinity. Here is what the mission statement of the APA group that studies men and masculinity says:

“Acknowledges its historical debt to feminist-inspired scholarship on gender, and commits itself to the support of groups such as women, gays, lesbians and people of color that have been uniquely oppressed by the gender/class/race system.”

I don’t mind professionals being interested in this or that theory but what I do mind is when that theory becomes a sacred cow which limits open discussion. On the mailing list of Division 51 feminism was that sacred cow. It was highly discouraged to question anything about feminism. It was also not a good idea to make any references to possible biological factors in masculinity, or to consider men worthy of choice and compassion. None of those flew very well. Actually a man, a PhD, was banned from the list for bringing up male victims of domestic violence too many times. Hard to believe but in the wacky wonderland of the feminist Division 51 it is totally true.

During my time on this list I would receive emails from other list members who did not post to the list but wanted me to know that they appreciated my willingness to question the feminist ideas and stand up for boys and men. They all said the same thing. “I wish I could post to the list and support you but I fear for my professional career.” They were worried that the bullies on the list, which included a number of very prominent psychologists, would blackball them. This tells the story of this list. It is run by bullies who try and force messages to the list to conform to the feminist standard. Many list members are very aware of their power and simply lay low.

It is of critical importance that every person interested in the MHRM knows that our professional psychological community routinely blames men and boys and expects them to change and be more like women in order for the world to advance. Much of the research being done has this underlying attitude as do the “experts” that are called on by the mainstream media, and also many of those who are doing therapy with men and women. It will take a great effort to expose the misandry that is embedded in their ideas and related practices. The more these ideas can be challenged publicly the better. We need our helping professionals to have concern and love for both sexes, not just one.

Now that we have a better idea of the origins for these four categories let’s get back and take a look at more of the ways that misandry underlies this inventory.

The Focus Groups

How had Mahalik come up with these categories? Were variables such as “power over women” and ”violence” pulled out of thin air, from the ideas of toxic masculinity, or was there some other rationale behind their selection? Had there been any attempt to choose norms that fit with white heterosexual men of all age across the United States? The article states that the researcher first reviewed the professional literature on masculine norms and then started two focus groups to discuss and refine them.

The groups met for 90 minutes each week for 8 months with the researcher. The curious part of this is that of the nine people in these two focus groups, only 3 were white men! Five of the nine were women. Here is the demographic composition of each focus group: (Group 1) 1 Asian American man, 1 European American man, 2 European American women; (Group 2) 2 European American men, 2 European American women, 1 Haitian Canadian woman.

Notice that men are in the minority and that white men make up only 1/3 of those in these focus groups. Importantly, white men are in the minority even within each focus group. This is odd, to say the least, considering that the overtly claimed goal was to develop norms of European American men. Why include so many women? Why have the group that you want to study be the minority? I started to wonder if the researcher had some pre-conceived ideas that he wanted to propagate. I wondered if having too many men and especially too many white men, after all, might foil his attempt to plant the seeds of his favored ideology? Who knows but it is a gaping question why white males were so underrepresented.

To see the absurdity of having white males be only 1/3rd of the focus group participants let’s try an exercise. Imagine that the same researcher is studying African American norms. He puts together focus groups to try and refine these norms. He has 3 African Americans, 4 whites, 1 Korean, and 1 Hispanic. These nine people form two focus groups where the African Americans are in the minority of both groups. It’s simple to see how that could be considered racist and intentionally marginalizing African Americans. It’s simple to see that groups such as that would be less likely to come up with an accurate representation of norms for African Americans than a group that solely consisted of African Americans might be able to provide. I hope it is also simple to see the misandry of this researcher’s using a minority of white males in the focus groups.

It’s worth noting that these focus groups included only grad students in counseling psychology. According to an e-mail from Mahalik, moreover, all were in their mid-20s. In a nutshell, the groups lacked diversity in age. Hardly the sort of group one would want to make decisions about the norms for all ages of white American boys and men.

Inventing the CMNI, supposedly an academic enterprise, were young men and women who relied on their own moral and ideological judgments about masculine norms. A better name for the result would be the Conformity to Adolescent Masculine Norms Inventory. Some of the conclusions that it presupposes do make sense when applied to immature and adolescent boys. Middle school boys may exhibit similar sorts of immature behavior. In some ways that is normative for that age group. Perhaps the authors are simply unaware of and have little experience with the mature masculine? We simply don’t know that at this point. What we do know is that the inventory, whatever its origin, is misandrist.

Mahalik also created an inventory for women, the Conformity to Feminine Norms Inventory. It gives us a way to understand the CMNI more deeply by comparing it to the related CFNI. That is what we will do next.

CFNI Female Conformity to Norms Inventory

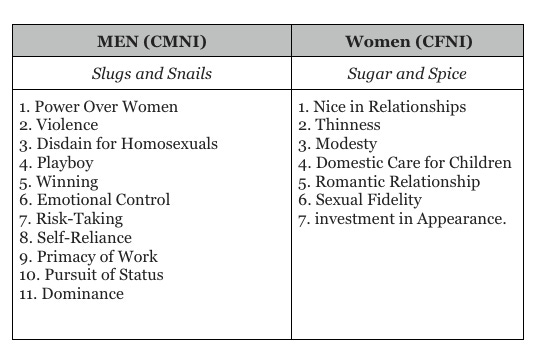

When I first saw the CNMI, I was a shocked at the misandrist content but wondered if that was merely a millennial shift for the 21st century toward examining the shadowy, unconscious aspects of life. That thought was dashed, though, when I saw the companion inventory for this the CFNI (Conformity to Femininity Norms Inventory), which the same researcher had created. I wondered if this version, for women, would contain similarly negative and judgmental “norms” for them. Would it refer to gossip, relational violence, the queen bee, or the gold digger as norms? What I found was that these norms were almost completely positive, all sugar and spice. Here is a list of them:

nice in relationships

thinness

modesty

domestic care for children

romantic relationship

sexual fidelity

investment in appearance.

All of these “norms” are either flattering to women or neutral. There is not a hint of judgment towards women in the naming of these feminine norms. All of them could be manifested robustly without causing harsh judgments. A woman could invest greatly in her appearance and be very concerned about her sexual fidelity or children or her modesty and she would be considered fine and dandy by our culture’s standards. Contrast this with the men’s “norms” such as violence where even a little of that “norm” is a horrible thing that deserves scorn and harsh judgment. I won’t argue if these feminine norms are right or wrong, only that they are distinctly different from the norms for the men and are much more positive and non threatening towards women.

It seemed to me that the researchers were reluctant or even afraid to make any negative claims about traditional feminine norms. Even more interesting was the way in which Mahalik established these norms for women. He created focus groups, as he had done for men, but this time he included students of only one sex, only women. These focus groups had a wider range of ages, moreover, and included middle-age women. The mean age was 32 with a standard deviation of 10 years. This means that most of the group members were likely between 18-46. Indeed, the women were asked to join not two but five focus groups. Several groups included mainly young women. Two included adult women from the community. Unlike the male focus groups, these represented more than the adolescent population. Somehow Mahalik switched gears and only chose women for the focus groups for the CFNI. I wonder what sort of reaction might have come if women were in the minority of each of the five focus groups?

Comparing the CMNI and CFNI

Both inventories used focus groups to refine the norms that would be used. In the masculine version (CMNI) the focus groups included many women. In its counterpart, the feminine version (CFNI), these groups included only women. One would think that if you wanted to get a clear idea of the norms of a group you would want members of the group under study to make those assessments. To create a group deliberately with most members coming from outside the group almost defies explanation. I e-mailed Mahalik about this. He never responded directly to my question.

Focus groups for the CFNI had a greater age range than those for the CMNI. It is easy to assume that the older women would have a markedly different perspective on feminine norms from that of the younger women. The younger men and women in focus groups on masculine norms would be likely to have a very similar perspective: that of an adolescent.

The two inventories contained remarkably different “norms,” with the masculine ones being negative and judgmental and the feminine ones either flattering (despite being, according to feminists, inconvenient) or neutral. Why didn’t the feminine norms include any negative stereotypes, just as the masculine ones did? I found a hint about the reasons behind this from Mahalik in a section of the journal article about the CFNI.

In addition, because the CFNI is intended to measure conformity to traditional norms of femininity in the U.S., we thought it should also relate to women’s development of a feminist identity. In describing women’s feminist identity development, Downing and Roush (1985) proposed a five-stage model in which the first stage, passive acceptance, reflects acceptance of traditional European American, North American, gender roles, beliefs that men are superior to women, and that these roles are advantageous. The second stage, revelation, is in response to a crisis or crises that lead women to question traditional gender roles and to have concomitant feelings of anger toward men. Sometimes women in this stage also feel guilty because of how they may have contributed to their own and other women’s oppression in the past. The third stage, embeddedness-emanation, reflects feelings of connection to other women, cautious interactions with men, and development of a more relativistic frame of life. The fourth stage, synthesis, is when women develop a positive feminist identity and are able to transcend traditional gender roles. (page 425 Conformity to Feminine Norms Inventory)

This quotation is very different from my earlier one about the culpability of white men. The women are described as developing a “feminist identity” and learning that they have been living in a world that oppresses them. This is the first time identity has been connected to social norms and is only found in the CFNI, not in the men’s CMNI. The women are told that men and their traditional roles are what has been holding them back because of the belief that women are inferior. It is clear that the researchers frame women as “good” and in need of space to grow while at the same time framing men as “not good” and needing to change. It is also worth noting that good is now conflated with victim in the CFNI. The assumption is that women are inherently good, and this goodness manifests more robustly when they can transcend the oppression they have suffered at the hands of males. This creates a picture of a good human being who is perpetually victimized by “the way things are.” It is this sort of characterization that allows feminists to paint women as good and also in need of protection and special services. Sadly these two inventories boil down to the creaky dichotomy between good women and evil men. Cartoons, in short, have made their way into academia. Let’s just look briefly at the norms chosen for women and the norms chosen for men and compare the two:

I am going to avoid comparing these and will leave it to the reader to draw their own conclusions. I will say that the Nursery Rhyme for each seems to describe the contents fairly well. How far have we come since the days of Nursery Rhymes?

It was obvious to me that a part of the misandry of this inventory was in the choice of names for the different categories. But it dawned on me to examine whether the actual questions on the CMNI were connected to the names. The first one I thought of was disdain for homosexuality. I found myself wondering what questions you could ask in a questionnaire such as the CMNI that would allow you to determine if someone truly had disdain for homosexuals. I found the actual questions of the CMNI and guessed at which ones were related to the disdain for homosexuality category. You will see them below:

5. It is important to me that people think I am heterosexual

16. Being thought of as gay is not a bad thing

23. I make sure that people think I am heterosexual

37. I would be furious if someone thought I was gay

42. It would not bother me at all if someone thought I was gay

51. It would be awful if people thought I was gay

63. I like having gay friends

73. I would feel uncomfortable if someone thought I was gay

80. If someone thought I was gay, I would not argue with them about it

91. I try to avoid being perceived as gay

Each of those questions seems to ask about a man’s worry and fear over being seen as gay. Please note that none of them are remotely related to a man’s “disdain” for homosexuals. Disdain is defined as having to do with contempt, scorn, or some might even say hatred. But do those questions in any way evaluate the respondents contempt, scorn or hatred? I would say no, but somehow the researcher seems to ask that series of questions and then label those who answer that they are indeed fearful of being seen as gay that they have disdain for homosexuality. This is ridiculous. Someone can be afraid of tigers and not hate them. They can be afraid of lightning and not hate it. The two are very different and this is one more example of this inventory’s questionable construction. It seems to me that it would be like asking a group of people if they were afraid of bumblebees and then labeling them bumblebee haters if they answered that they were afraid.

Yet another questionable part of this inventory can be seen when we compare the questions of the CMNI with those of the CFNI. If we look at the questions for the Playboy section of the CMNI and compare it to the questions in the Sexual Fidelity portion of the CFNI we find that the two sections have almost identical questions. Here they are:

PLAYBOY - CMNI

3. If I could, I would frequently change sexual partners

13. An emotional bond with a partner is the best part of sex

28. If I could, I would date a lot of different people

33. I would only have sex if I was in a committed relationship

38. I only get romantically involved with one person

47. I would feel good if I had many sexual partners

58. Long term relationships are better than casual sexual encounters

66. Emotional involvement should be avoided when having sex

83. A person shouldn’t get tied down to dating just one person

90. I would only be satisfied with sex if there was an emotional bond

SEXUAL FIDELITY - CFNI

4. I would feel extremely ashamed if I had many sexual partners

21. I prefer long-term relationships to casual sexual ones

29. I would feel guilty if I had a one-night stand

39. It is not necessary to be in a committed relationship to have sex

47. I would feel comfortable having casual sex

50. Being in a romantic relationship is important

56. I frequently change sexual partners

65. I would only have sex with the person I love

67. When I have a romantic relationship, I enjoy focusing my energies on it

72. It would be enjoyable to date more than one person at a time

78. I would only have sex if I was in a committed relationship like marriage

Some of the questions are exactly the same and some are simply worded differently but are asking very similar sorts of things. But the titles are very different. Calling one of these categories sexual fidelity and the other playboy seems very suspect. Why not call them both what they are, an assessment of sexual fidelity? Either call them both sexual fidelity or change the female title to something that matches the playboy title. What is a female who has lots of relationships called? Well, a hussy or a slut. Name it sluts and playboys! I bet that would have gone over very big with the feminists but the playboy label doesn’t seem to draw much ire does it?

Conclusion

It seems clear that misandry is embedded in this inventory. When I wrote messages on the APA mailing list for men and masculinity that questioned this inventory and pointed out many of the things you have seen in this article I was told that there was no misandry. I think this article clearly shows their claims are indeed false. There is misandry in this inventory and it is clear for all to see. That these professionals were unable to admit to this is yet more proof of the academic psychological community being enablers of females and feminism in the worst sort of way. The problems started as feminist writing and thought started to influence the thinking of psychologists. This resulted in the adoption of feminist thinking about men which then resulted in rigid and misandrist attitudes about men and the resulting misandry we see placed in this inventory. I simply can’t see any other explanation for the willingness to lump an entire birth group into such negative categories. If this sort of thing were done to any other group of people, the result would be immediate negative reactions from the groups involved and the press with multiple calls for apologies. However, when it is done to men we hear nothing of the sort. The problem can be likened to an ideological infestation. It is not merely popular culture, which everyone likes to attack, but also elite culture—that of academics, lawyers, politicians, social workers—and psychologists. We need to move to a point where we can see both men and women, masculine and feminine as having positive and negative qualities and learn to value each individual. We have a long way to go. You can help things along by speaking out.

Final Word on This Series

The three research articles that have been discussed in this series have one thing in common. They all rely on an ideological assumption, which the researchers try to bolster and confirm. In the process, they ignore the needs of men and boys by heaping contempt, either implicitly or explicitly, on masculinity, maleness or both. In the first study, on teen dating violence the questionnaires offered convincing data that boys were victims. But the researchers ignored that. Instead, they relied on a preferred ideology, one that assumes the primacy of female victims and therefore (despite the non sequitur) the primacy of their need for more care than male victims (if, so goes the argument, there are any male victims at all). In the second study we examined on reproductive coercion, researchers relied on the ideological belief that women are victims and men perpetrators, and their study showed just that, but they used an impoverished population that in no way generalizes to the population at large. Even though the researchers were aware of this limitation, the press release and articles by journalists ignored this limitation and treated the study as if it were indeed generalized. This was a huge boon for those researchers who wanted to “spread the word” of their chosen ideology. I can hear them saying, “Well, it was not exactly portrayed correctly but, you know, it was for a good cause.” In other words, the end justifies the means. Then the third article on the CMNI showed distinct signs of misandry in psychological research. The researcher believes that masculinity, or at least the version of masculinity that he considers prevalent in our society, is to blame for our problems. Consequently, the CMNI becomes a way of promoting an ideology.

The problem is that these researchers are standing science on its head. Real science requires astute and unbiased observers, who are eager to find the truth wherever the search leads them. This stands in stark contrast to ideologically based “studies” that use science as a means to some political end. This is very dangerous, in my opinion, but not enough people are aware of what is happening. Confidence in scholarship must be earned, continually, by scholars themselves. Even my confidence in my own field has declined. Scholars must be vigilant and not allow those who grind political axes to promote their own ideologies in the name of scholarship. But that’s not all. Journalists, too, must wake up. In fact, everyone must participate in the renewal of intellectual and moral integrity in academe.

Men Are Good.

REFERENCES

One of the best summaries of the ways that misandry is found in current psychological research is found in Appendix Three of Nathanson’s and Young’s Legalizing Misandry. The title of that appendix is “Misleading the Public: Statistics Abuse”

1. Nathanson, Paul & Young, Katherine R. (2001), Spreading Misandry: The Teaching of Contempt for Men in Popular Culture, Harper Paperbacks, Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, ISBN 9780773530997

2. Nathanson, Paul & Young, Katherine R. (2006), Legalizing Misandry: From Public Shame to Systemic Discrimination against Men, Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, ISBN 9780773528628

3. Fiebert Bibliography which contains abstracts of over 150 studies many of which show that women initiate domestic violence at a greater rate than men

4. August 3, 2007 American Psychiatric Association article pointing out that among violent couples women were more often the aggressors. (See the image below)

5. Archer, J. (2000). Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 651-680. (Meta-analyses of sex differences in physical aggression indicate that women were more likely than men to “use one or more acts of physical aggression and to use such acts more frequently.” In terms of injuries, women were somewhat more likely to be injured, and analyses reveal that 62% of those injured were women.)

6. This page is a Montgomery County Maryland sponsored page which falsely claims that men are over 95% of the perpetrators of domestic violence. This page has recently been edited and moved. see the original image below.

7.Mahalik, J.R., Locke, B., Ludlow, L., Diemer, M., Scott, R.P.J., Gottfreid, M., Freitas, G. (2003). Development of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 4, 3-25.

8. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services statistics on child abuse/murder, This page has been moved. Here is a jpg of the original chart.

9. Harris, Ian. Messages Men Hear: Constructing Masculinities (Gender, Change and Society)Taylor and Francis, 1995.