The Study That Was Twisted: How CNN Turned “Exposure” Into “Toxic Masculinity”

In October, 2025, CNN ran a commentary by communication professor Kara Alaimo claiming that boys exposed to “digital masculinity” online have lower self-esteem, are lonelier, and that such content fuels offline violence against women. The problem? None of that is what the data actually show.

Alaimo based her argument on a Common Sense Media survey titled “Boys in the Digital Wild: Online Culture, Identity, and Well-Being.” After reading both the CNN piece and the full 88-page report, the contrast couldn’t be sharper. What she presented as a story of crisis looks, in the actual data, like a story of ordinary adolescent life — with a few predictable patterns and a lot of healthy boys.

What the Survey Really Found

The 2025 report surveyed 1,017 boys ages 11–17 across the U.S., asking about their online habits, exposure to “masculinity-related” content (posts about fighting, fitness, dating, or making money), and indicators of well-being such as self-esteem and loneliness.

Here are the key numbers:

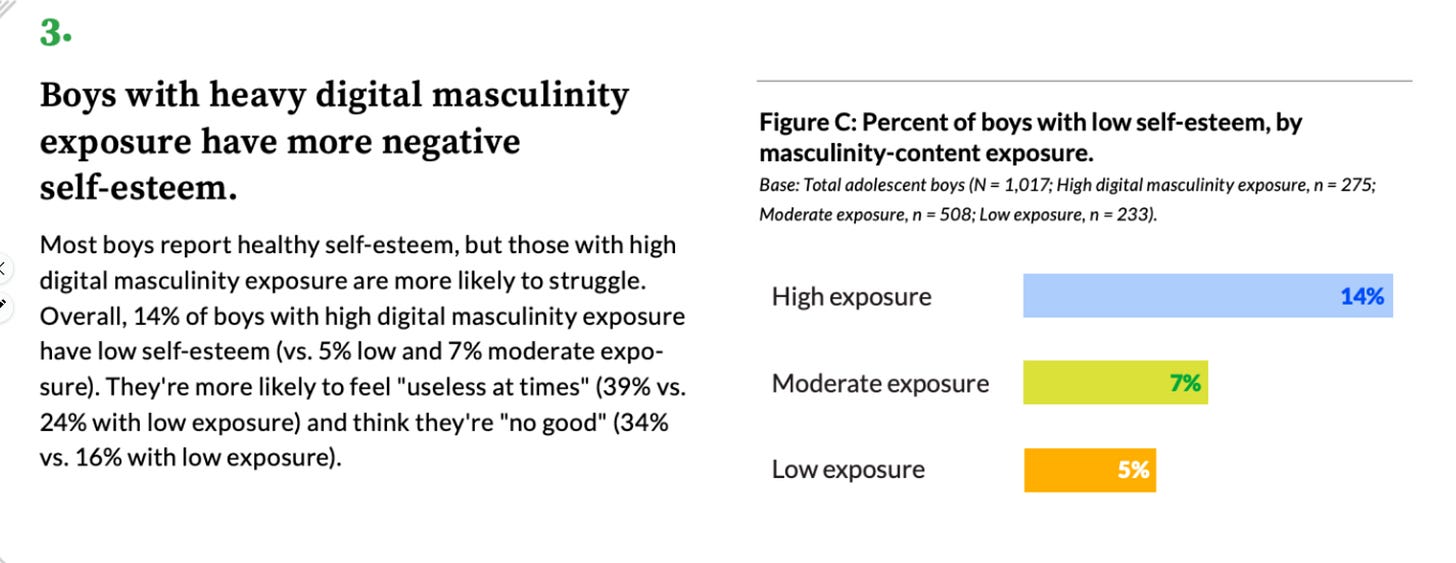

86 % of boys with “high exposure” to masculine themed content had normal self-esteem. Only 14 % showed low self-esteem — a small minority.

Over half reported feeling belonging and liking who they are online.

68 % said this content “just appeared” in their feeds; they weren’t seeking it.

“Boys still embrace caring behaviors, with 62% believing in being friendly even to those who are unfriendly to them, 55% putting others’ needs before their own, and 51% caring about others’ feelings more than their own.”

Strong offline mentorship predicted the healthiest outcomes.

Fathers ranked highest as the most admired and trusted role models — more than celebrities, influencers, or athletes — showing that boys still look to their dads for guidance and identity.

In short, the majority of boys are fine. A small group shows some struggles. The strongest predictor of resilience isn’t censorship or re-education — it’s healthy offline relationships.

What the Survey Didn’t Measure

This part matters most: The survey never asked whether boys believed or endorsed the content they saw. It only asked if they had encountered it. Exposure does not equal endorsement.

Seeing a video about boxing, entrepreneurship, or dating advice says nothing about whether a boy admires or rejects it. Yet Alaimo’s article blurs that crucial distinction. She assumes that viewing equals internalizing — that the algorithm shows, and the boy obeys. That’s not science; it’s projection.

How CNN Distorted the Findings

Alaimo’s piece takes mild statistical associations and turns them into moral certainties. Here’s how:

What the report actually said: 86 % of high-exposure boys did not have low self-esteem.

What CNN claimed: “Boys with higher exposure have lower self-esteem and are lonelier.”

Why that’s misleading: It turns a small correlation into a blanket statement.

Here’s the image from the survey:

Note that the study itself said most boys had healthy self-esteem, and that 14% of high-exposure boys reported low self-esteem—which means 86% did not. Alaimo’s claim would have been accurate if she had written that a slightly higher percentage of high-exposure boys reported low self-esteem compared to moderate- and low-exposure groups. But she didn’t. Instead, she stated flatly that high-exposure boys have lower self-esteem. That isn’t honest reporting—it’s a distortion that misleads readers into believing the data showed something it didn’t. Here’s the quote from the CNN article:

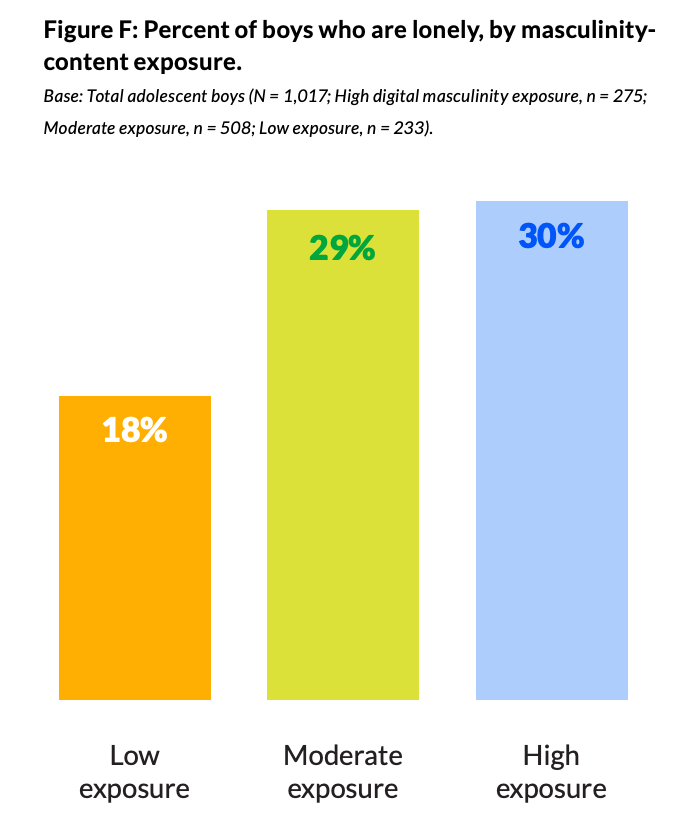

She did the same thing with the loneliness issue. The survey showed that 70% of high exposure boys were not shown to be lonely. But this didn’t keep Alaimo from claiming that higher exposure to masculine content made boys more lonely. Here’s the graphic from the survey:

In another part of the article Alaimo says the following:

When you follow the link she labels as “my research,” there’s no actual study showing that negative messages about women and girls cause offline violence. The link leads instead to another article summarizing her opinions on the topic. While she refers vaguely to a “wide body of research,” none of the studies she mentions establish a causal connection between online content and real-world violence against women. In fact, the evidence she cites is general research on media violence, not on misogyny or social media behavior.

Alaimo seems intent on frightening parents into believing that if their sons spend time online, they’ll absorb misogyny like secondhand smoke—emerging damaged, insecure, and primed for violence against women. It’s a manipulative narrative built on fear, not evidence. What parent wouldn’t feel alarmed by such a claim? And yet, that fear is precisely the tool being used to steer boys away from open spaces where they might think and speak freely.

Here are some more distortions:

• What the researchers cautioned: “The study cannot prove causation.”

→ What CNN implied: Digital masculinity causes low self-esteem—and even violence against women.

→ Why that’s misleading: It ignores the study’s explicit caveats.

• What the study measured: Exposure, not belief.

→ What CNN wrote: As though boys automatically absorbed misogynistic messages.

→ Why that’s misleading: It substitutes ideology for data.

• What the report also noted: Online spaces provide connection, belonging, and skill-building.

→ What CNN left out: The most positive findings.

→ Why that’s misleading: It works to create a one-sided moral panic.

What the Study Actually Emphasized

The Common Sense Media team didn’t call for censorship or surveillance. Their conclusion was strikingly balanced:

“With thoughtful intervention from parents, educators, policymakers, and industry, we can help boys navigate these digital environments while maintaining the human connections essential to their well-being.”

In other words, mentorship matters most. They recommend encouraging offline friendships, sports, robotics, and other group activities — spaces where boys can build confidence and identity without online distortion.

Alaimo’s takeaway? By the end of the article, she does encourage offline group activities—but the damage was already done. Readers were left with the clear impression that the manosphere is a dangerous place. This fits neatly with what appears to be her larger goal: to discourage parents from allowing boys to engage with those online spaces and to steer them back toward environments where the narrative is safely controlled.

A Pattern of Ideological Storytelling

This is not the first time feminist commentary has blurred the line between seeing and believing, between association and causation.

It’s part of a broader cultural reflex: assume that anything linked to masculinity must be toxic. When an adolescent boy shows interest in strength, competition, or success, the narrative pathologizes it as “hypermasculine.”

But strength, drive, and mastery are not dangerous traits. They are the same impulses that lead boys to protect, to build, and to grow — when guided by good mentors.

The Real Story: Boys Need Connection, Not Correction

What the data actually tell us is simple and deeply human:

Boys are online, yes. Some of what they see is rough, crude, or confusing. But most are fine. What they need most are adults — fathers, coaches, teachers, uncles, community leaders — who can talk with them about what they see, help them think critically, and model a balanced kind of strength.

When commentators like Kara Alaimo twist research into another attack on masculinity, they don’t protect boys — they alienate them further. They feed the very disconnection the data warn against.

Bottom Line

The Common Sense Media report offers a nuanced view of how boys navigate digital life. The CNN piece that claimed to summarize it turned that nuance into ideology.

The study: “Most boys are doing fine; let’s support them.”

The article: “Masculinity is toxic; it’s making boys and women unsafe.”

That’s not journalism. It’s advocacy in disguise — and it’s time readers started calling it what it is.

Why Feminist Commentators Fear the Manosphere

When CNN commentator Kara Alaimo warned that “digital masculinity” is harming boys, her real anxiety wasn’t about boys at all. It was about control.

The loss of gatekeeping power

For decades, feminist scholars and journalists held near-total control over how gender was discussed in mainstream culture. University departments, newsrooms, and social-media policy boards all spoke from the same script: masculinity is a problem to be corrected; feminism is the solution.

Then the internet happened. Podcasts, YouTube channels, Substack pages, and online forums created an uncontrolled space where men could speak to one another about purpose, rejection, fatherhood, meaning and a host of other topics that were forbidden in traditional places. Some of those voices are clumsy or angry, but many are thoughtful and compassionate—addressing needs the establishment had ignored.

To academics like Alaimo, that independence looks like rebellion. What she calls “the manosphere” isn’t a hate movement; it’s a marketplace of ideas she can’t supervise.

Shaming as a tool of control

When direct censorship fails, moral shaming becomes the fallback. The labels—toxic, dangerous, extremist—are meant to end the conversation before it starts.

Alaimo’s CNN piece is a textbook case: she takes a mild statistical correlation from a Common Sense Media survey and turns it into a moral warning that “masculinity online” makes boys lonely and violent.

This isn’t social science; it’s social conditioning. The goal is to make boys feel guilty for showing interest in strength, fitness, or ambition—traits that once defined healthy manhood. Curiosity becomes complicity. Click on a video about discipline, and you’re suddenly part of a “radicalization pipeline.” It also sends a message to parents that they need to control their boys online activity or face his loneliness, low self-esteem, and violence.

Projection and double standards

What often goes unnoticed is how these writers display the very hostility they accuse men of harboring. They generalize, moralize, and treat half the population as a threat in need of supervision. When men question feminist orthodoxy, it’s labeled hate. When women condemn men collectively, it’s celebrated as activism.

This double standard isn’t born of hatred so much as fear—the fear of losing moral authority. The manosphere’s unforgivable sin isn’t misogyny; it’s disobedience.

The real reason the manosphere exists

Men aren’t gathering online to plot against women. They’re doing it because they’ve been shut out of the cultural conversation. Schools tell them they’re privileged; therapy often tells them they’re defective; the media tells them they’re dangerous. The online world, for all its rough edges, at least lets them talk back.

The healthiest parts of that space offer something our institutions once did naturally: mentorship, brotherhood, challenge, and purpose. Those are not extremist ideas—they’re human needs.

What this panic reveals

When writers like Kara Alaimo insist that masculinity itself is the problem, they reveal more about their ideology than about boys. The panic over “digital masculinity” is the sound of a monopoly losing its grip. As soon as men can define themselves without approval from the establishment, the establishment cries harm.

But the truth is simpler: boys are searching for models of competence and belonging, and they have every right to look for them wherever they’re found.

The path forward

We don’t need another crusade against masculinity. We need more honest conversation—without the gatekeepers, without the shame, and without the moral panic. Let the data speak, let the boys speak, and let men continue the long-overdue work of reclaiming a healthy sense of who they are.

Men and Boys are Good