Institutional Sexism: The Bias We’re Not Allowed to See - Part 3 - Conclusion

If institutional sexism against men is so pervasive, why can’t we see it?

Why can a society capable of diagnosing “microaggressions” and “implicit bias” remain blind to its own structural prejudice against half its citizens?

The answer lies in a deeper psychological bias — one older than feminism and broader than politics. It’s the instinct to center women’s needs first: gynocentrism.

Gynocentrism isn’t hatred of men; it’s compassion with blinders on. It’s the moral reflex that sees women as fragile, men as durable, and suffering as legitimate only when it’s female. It shapes our empathy map from childhood — the little girl who cries is comforted; the boy who cries is told to toughen up. By adulthood, that reflex is baked into the culture.

When feminists in the 1960s began describing institutions as oppressive to women, they were building on this foundation. The public accepted the narrative easily because it fit the moral intuition that women need protection and men need correction. The idea of institutional sexism against women felt right; the idea of institutional sexism against men felt absurd.

But intuition isn’t truth.

Gynocentrism acts like an ideological shield: it protects women from scrutiny while leaving men exposed. When a woman fails, the system failed her; when a man fails, he failed himself.

The result is a self-reinforcing loop — a feedback mechanism that rewards female victimhood and punishes male vulnerability.

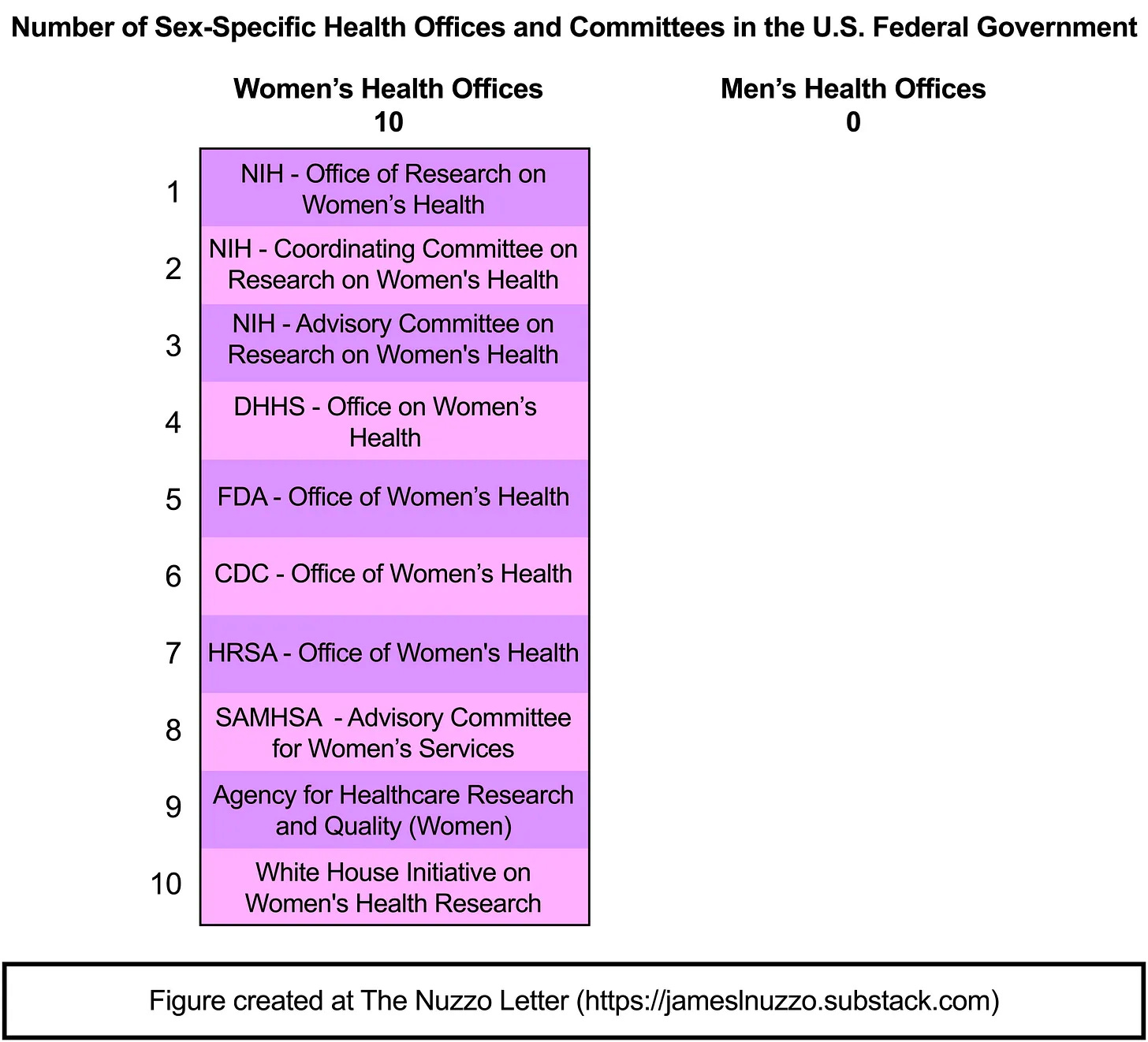

Even academia, which claims neutrality, is steeped in this moral reflex.

Gender-studies programs that once promised to challenge inequality now function more as temples of ideological maintenance. Their role is not to question whether men face systemic bias, but to explain away any data suggesting they do. The assumption is always that men hold the power, even when they demonstrably don’t.

That’s not scholarship; it’s theology.

And like all theology, it protects itself by defining heresy. The heretic, in this case, is anyone who points out that compassion has been rationed by sex.

7. The Human Cost

When systems consistently favor one sex’s pain over the other’s, people learn. Boys learn it first.

They learn it in classrooms that scold their energy and reward compliance.

They learn it in media that depicts them as bumbling, violent, or disposable.

They learn it in families where fathers are peripheral, or where mothers wield the quiet authority of assumed virtue.

By adulthood, many men have absorbed the lesson: your feelings are a burden, your needs are negotiable, your failures are proof.

This is how institutional sexism becomes internalized.

Men stop expecting fairness, and worse, they stop expecting empathy. When injustice occurs — in courts, workplaces, or relationships — they don’t see it as systemic. They see it as personal failure or weakness.

That resignation is perhaps the cruelest outcome of all.

Because institutions don’t have to oppress loudly when their subjects have already consented to being overlooked.

The emotional toll is enormous but unmeasured. It shows up in statistics — suicide rates, addiction, homelessness — but the deeper wound is existential. When a man realizes that the society he contributes to has little instinct to protect him, something vital in his spirit hardens.

As one father told me after losing custody of his children, “I didn’t just lose them. I lost faith in the idea that fairness even applies to me.”

Institutional sexism isn’t only about policies. It’s about the quiet message that some lives merit more compassion than others. And that message, delivered generation after generation, corrodes our collective sense of justice.

8. Reclaiming the Term

It’s time to reclaim the language.

If systemic bias means patterns of disadvantage embedded in structures, then we must be willing to name those patterns wherever they occur — not just where they fit a fashionable narrative.

Institutional sexism should never have been gendered. It describes a process, not a direction: the way institutions absorb moral assumptions and translate them into policy. Sometimes those assumptions favor men. Increasingly, they favor women. The honest mind must be able to see both.

Reclaiming the term doesn’t mean denying women’s or men’s historical struggles. It means applying the same analytical lens to everyone. It means intellectual consistency.

We’ve built a society where calling attention to male disadvantage is considered controversial, while calling attention to female disadvantage is considered virtuous. That asymmetry is itself a form of institutional sexism — the kind that hides behind moral approval.

The first step toward balance is honesty. We must be willing to ask the forbidden question:

If equality truly matters, why are we afraid to see when the system tilts against men?

If we can’t even name institutional sexism when it harms half the population, then the word equality has lost its meaning.

The goal isn’t to replace one victim class with another. It’s to restore integrity to the moral compass of our institutions — to remind them that fairness, by definition, cannot be selective.

Closing Note

Perhaps someday, a university course on “institutional sexism” will examine both sides honestly. Students will study how empathy, once a virtue, became gendered; how compassion was politicized; how language turned from a tool of truth to a weapon of ideology.

Until then, it falls to those outside the institutions — writers, thinkers, fathers, teachers, ordinary men and women — to hold up the mirror.

Because the greatest act of equality is not claiming more compassion for one sex.

It’s extending it, finally, to both.