Every now and then, a simple classroom exercise reveals something profound about human nature. Jane Elliott’s famous “blue-eyes/brown-eyes” experiment did exactly that. Many of you will remember it: the day after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, Elliott, a third-grade teacher in Iowa, decided her students needed to understand prejudice in a way a lecture could never accomplish.

So she divided the children by eye color.

One group was told they were smarter, kinder, and better behaved. The other group — their own classmates and friends — were told they were not. Nothing about the children changed except the message they were given.

That was enough.

Within minutes, the “favored” students stood taller and spoke more confidently. They completed work more quickly and volunteered answers with pride. The disfavored group wilted. Their shoulders rounded. Their test scores dropped. Some withdrew, others grew angry. A few even began to believe the negative things said about them.

Elliott hadn’t created new children. She had created a new context — one in which the adults in power defined who deserved approval and who didn’t.

The experiment showed something we often forget: children are exquisitely sensitive to the attitudes and expectations of the people who guide them.

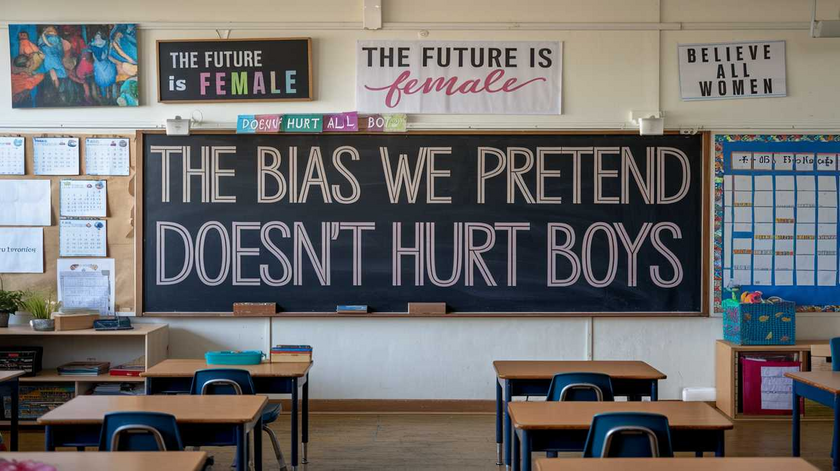

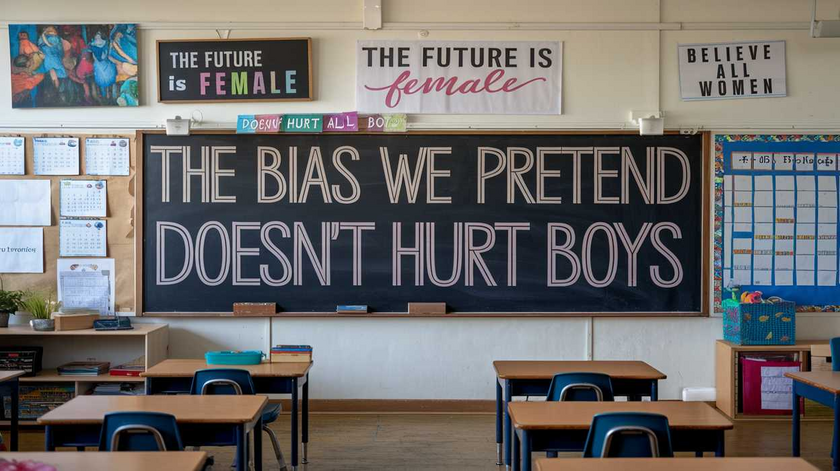

Even subtle cues from authority can become destiny. A raised eyebrow, a dismissive tone, a slogan on the wall — all of it shapes who children believe they are allowed to be.

Elliott’s students went through only a single day of being “favored” or “disfavored,” and it changed their behavior, confidence, and even cognitive performance.

Imagine, for a moment, what would happen if one group of children lived like this not for a day, but for years. Imagine if the message they heard — from teachers, media, curriculum, and culture — told them that something essential about them was wrong.

Imagine if they were boys.

That’s where we’re headed. But before we get there, we need one more piece of the puzzle.

Because psychologists later discovered that what Elliott demonstrated dramatically in a classroom is also happening quietly inside children every day. They even gave it a name.

It’s called stereotype threat.

And it explains far more about our boys’ struggles — and our cultural blind spots — than most people realize.

What We Learned From Girls and Math

Stereotype threat is a simple idea with enormous consequences.

It refers to what happens when a person fears confirming a negative stereotype about their group. That fear — often subtle, often unspoken — increases anxiety, reduces working memory, undermines confidence, and lowers performance.

It is not about ability.

It is about expectation.

And most people first learn about stereotype threat in one particular context: girls and math.

For decades, girls were surrounded by the quiet cultural rumor that “girls aren’t good at math.” Teachers didn’t always say it directly. They didn’t have to. It floated around in a thousand small ways: textbook examples, facial expression, who was called on in class, who was encouraged and who was consoled. Girls absorbed it the way plants absorb light.

Researchers found that when girls were subtly reminded of this stereotype—even by something as small as checking a gender box at the top of a math test—their scores dropped. Anxiety went up. They second-guessed themselves. They disengaged.

The story was not about intelligence.

It was about identity under pressure.

The response from the educational system was swift and well-funded. Millions of dollars flowed into programs designed to counteract the stereotype threat girls faced in math:

teacher trainings

new curricula

role model programs

classroom redesign

mindset interventions

special grants

girls-only STEM groups

national awareness campaigns

All created to make sure young girls never again felt that mathematics was “not for them.”

And let me say this clearly: I support that work completely. No child should carry the weight of a negative stereotype when they’re simply trying to learn.

But something interesting happened.

As we were rallying national resources to eliminate a relatively narrow, subject-specific stereotype affecting girls in one academic domain….we failed to notice a far larger, far more toxic stereotype spreading over boys.

A stereotype not about arithmetic or algebra, but about their very nature.

A stereotype not whispered quietly, but broadcast loudly.

And unlike the stereotype about girls and math, this one has no funding, no programs, no protections, and no advocates in the institutions that shape boys’ lives.

That brings us to the part of the story almost no one wants to discuss.

The Stereotype Threat No One Will Name: What Boys Hear Every Day

If stereotype threat can undermine a girl’s confidence in math, imagine what happens when the stereotype isn’t about a subject…but about who you are.

Unlike girls, boys today aren’t navigating a single academic stereotype. They are navigating a cultural identity stereotype — one that targets their character, their intentions, their value, and their future.

And it’s everywhere.

Walk into almost any school, turn on almost any youth-oriented media channel, look at the messaging in teacher trainings, HR seminars, political slogans, and popular entertainment. The language aimed at boys is unmistakable:

“Boys are toxic.”

“Masculinity is inherently dangerous.”

“Men are oppressors.”

“Patriarchy is your fault.”

“You are privileged, even when you’re struggling.”

“The future is female.”

“Believe all women”

“We need fewer men like you and more women in charge.”

“Boys don’t mature, they get socialized into violence.”

Imagine hearing messages like this from every angle: teachers, counselors, the news, college brochures, viral videos, and political speeches. Even prime-time awards shows repeat the same theme: something is wrong with boys and men.

This is not a stereotype about ability. This is a stereotype about identity, morality, and worth.

And boys absorb it, like plants absorb the light.

Even the well-behaved ones.

The gentle ones.

The kind-hearted ones.

Perhaps especially the kind-hearted ones.

Because they are the ones who listen most closely to adult expectations. They care what adults think. And when every signal suggests there is something wrong with being male, boys begin to feel it in the same way Jane Elliott’s “less favored” children did:

some withdraw

some grow angry

some become depressed

some try desperately to prove they’re “safe”

some silence themselves around girls

some tune out and give up

Many learn to walk on eggshells.

Many learn to mask who they are.

Some feel ashamed before they even understand why.

This is stereotype threat on a scale our culture has never been willing to examine.

It undermines boys’ confidence not only in school, but in relationships, leadership, belonging, and moral value. It doesn’t hit one subject — it hits the entire self-concept.

And here’s the tragic irony:

When girls faced a stereotype affecting a single academic domain (math), our entire educational system mobilized. But when boys face a stereotype that frames their entire identity as suspect, dangerous, or defective…we look away.

Worse — we call it “progress.”

No grants.

No programs.

No protective messaging.

No teacher training on “encouraging healthy masculinity.”

No funding streams labeled “male resilience,” “male identity support,” or “boys’ psychological development.”

Nothing.

And yet we know from the psychology: stereotype threat doesn’t care which direction it flows. It hurts anyone subjected to it. Girls. Boys. Adults. Elders. Anyone.

The difference is that girls’ stereotype threat is treated as a national emergency, while boys’ stereotype threat is treated as an inconvenient truth best left unmentioned.

But the boys feel it.

They feel it deeply.

And it is reshaping an entire generation.

When you place a child in the “disfavored” group in Jane Elliott’s classroom, the effects show up almost immediately: withdrawn posture, lowered confidence, anger, sadness, and declining performance. Now imagine that same dynamic stretched across a childhood—not for a day or two, but for years.

That is what today’s boys are living through.

We’re watching the results play out right in front of us, but we rarely connect the dots. The signs are everywhere, yet hidden in plain sight:

Boys are falling behind academically.

Not by a little.

By a lot.

They earn:

lower grades,

fewer honors,

and far fewer college degrees.

Reading and writing gaps—never small—have now grown in size.

But we don’t ask whether constant negative messaging about male identity might be a factor. Instead, we say boys should “step up,” “apply themselves,” or “be less lazy,” as though shame has ever been a motivator.

Boys are disengaging from school.

Teachers say boys participate less. They’re more likely to tune out, act out, or withdraw. When a child believes he is viewed with suspicion, he stops coming forward.

This isn’t a mystery.

It’s textbook stereotype threat.

Boys are struggling socially.

A boy who believes his masculinity is problematic becomes hesitant. He won’t take risks socially. He won’t lead. He won’t assert himself. He won’t approach others. He is more likely to isolate or escape into online worlds where he is not judged simply for being male.

Boys are avoiding leadership roles.

They know one wrong move can be labeled “toxic,” “aggressive,” or “harmful.” So they hold back—especially in mixed-gender settings.

They self-limit long before anyone else has to.

Boys are losing their sense of belonging.

When you’re told repeatedly that your group is the source of society’s problems, you don’t imagine yourself as part of the community’s solution.

You imagine yourself on the outside.

Boys are suffering emotionally.

Rising rates of depression.

Rising rates of anxiety.

Rising suicide rates among adolescent boys.

And yet we never ask whether telling boys they’re dangerous or defective might be harming them psychologically. Just imagine telling any other group that the world would be better with less of them in it.

And then… boys stop asking for help.

Because why would you ask for help from a system that tells you that you’re the problem?

Boys, who already face the biological challenges of testosterone, the additional social push from precarious manhood, and the resulting male hierarchy, now carry an added layer of identity threat that undermines their confidence across every domain of life.

This isn’t subtle.

It isn’t accidental.

And it isn’t without consequences.

But here’s the part that should trouble us most:

We would never tolerate this treatment for girls. Ever.

If any institution—even unintentionally—sent girls negative messages about their identity, we would demand reform, new funding, and a national conversation.

But with boys?

We call it “accountability.”

We call it “progress.”

We call it “teaching them to be better.”

No.

It’s teaching them to disappear.

Part two will examine what creates and maintains this double standard.

Men Are Good.