This article discusses recent research on the male brain and fatherhood, offering further evidence that men nurture their children—just in a different way than women. It reminds me of The Life of Dad by Anna Machin, a wonderfully accessible book that explores research on fatherhood up until its publication in 2018. While this new study goes beyond Machin’s work, it echoes many of the findings she presented.

One key study Machin highlighted—but which is absent from this new research—involves oxytocin and how it influences mothers and fathers differently. When their children are young, both parents experience a surge of oxytocin when interacting with them, but their responses diverge. A mother’s oxytocin boost is linked to nurturing behaviors—stroking, verbal affection, and “motherese” speech—while a father’s oxytocin increase is associated with more active, physical engagement. Same hormone but very different responses. Evolution, Machin argues, tends to be efficient, avoiding redundancy. In other words, nature ensures that parents complement rather than duplicate each other’s roles: mothers nurture in one way, and fathers in another.

Until recently, the father’s approach to caregiving was often overlooked or even viewed negatively. However, researchers now recognize that fathers nurture their children through play, challenge, and boundary-setting—key behaviors that support healthy development and maturity. Some experts suggest that while mothers excel at raising children, fathers play a crucial role in raising adults. Despite this growing understanding, modern society continues to celebrate only the maternal style of nurturing. Yet, our children need both.

Researchers are increasingly recognizing the significant benefits of a father’s caregiving through rough-and-tumble play with his children. Studies have shown that this type of play helps children develop impulse control, frustration tolerance, emotional regulation, resilience, perseverance, and the ability to distinguish between playful and real aggression. Perhaps most importantly, it strengthens the bond between father and child.

The importance of these qualities becomes even more evident when considering the challenges faced by children growing up in fatherless households.

Another fascinating but often overlooked discovery is how both parents undergo psychological changes when a woman becomes pregnant. Studies on the Big Five personality traits have found that expectant mothers and fathers begin to shift toward greater alignment with each other, possibly to strengthen their teamwork as parents.

There is still so much we don’t fully understand about the roles of mothers and fathers—but research is finally catching up.

Here’s the article

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/2825647

November 13, 2024

How the Paternal Brain Is Wired by Pregnancy

Hugo Bottemanne, MD1,2; Lucie Joly, MD2,3

Author Affiliations Article Information

JAMA Psychiatry. 2025;82(1):8-9. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.3592

Pregnancy and post partum are accompanied by structural and functional brain changes in women that are thought to be important for caregiving.1 Studies have shown that pregnancy in women is associated with extensive gray matter volume reductions during pregnancy.1 Compared with controls, expecting mothers present lower cortical volume across several brain areas, with fewer cortical differences in the early postpartum period.1 Some of these brain changes have been correlated with increased attention to infant-related sensory stimuli, such as cries and odors.1 This neural plasticity and behavior change are driven by hormonal changes during pregnancy and can be distinguished from the brain changes caused by interactions with infants.1

A growing number of human brain imaging studies have focused on changes in the paternal brain after childbirth.2,3 Decreased gray matter in the orbitofrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, insula, fusiform gyrus, and left caudal anterior cingulate cortex and increased gray matter in the right temporal pole, hypothalamus, amygdala, striatum, subgenual cortex, superior temporal gyrus, and lateral prefrontal cortex4 were observed. Furthermore, first-time fathers showed a significant reduction in the cortical volume of the precuneus that was correlated with stronger brain responses in parental brain regions when viewing pictures of their own infant.3

A functional imaging study showed that fathers had preferential brain activation when exposed to infant-related vs non–infant-related stimuli, in contrast to nonfathers.4 Another study evaluating parental brain responses to infant stimuli in primary caregiving mothers, secondary caregiving fathers, and primary caregiving fathers who were raising infants without maternal involvement revealed that the latter group had greater activation in emotion processing networks toward their own infant interactions, akin to mothers.5 Taken together, these findings suggest that the time spent in childcare is a crucial factor in parental brain plasticity. In support of this hypothesis, a study revealed that childcare was positively correlated with the connectivity of the amygdala and superior temporal sulcus, regions associated with mentalizing and social perception processes.6

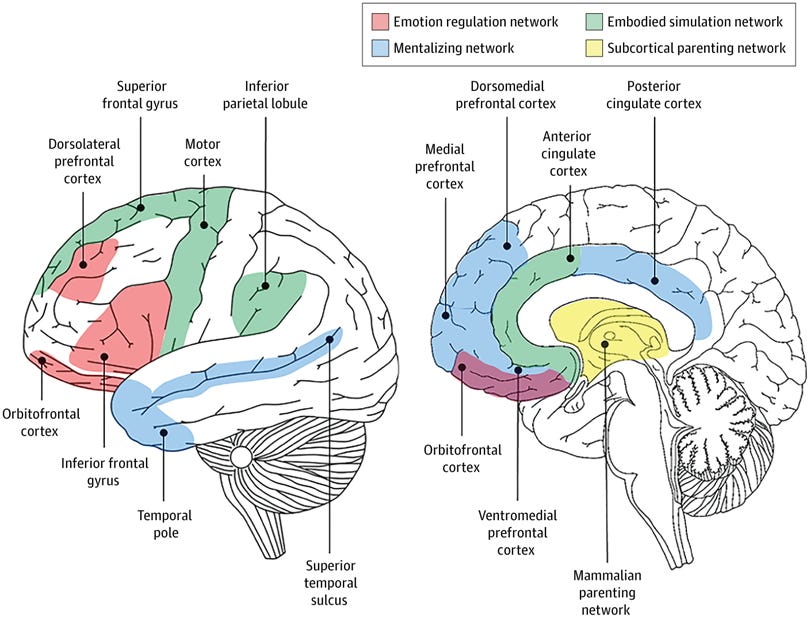

The aforementioned results support that paternal caregiving phenotypes rely on the same neural and hormonal substrates as maternal caregiving, referred to as the global human caregiving network.5 This network encompasses a mentalizing network (prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, temporal lobe, and superior temporal sulcus), an embodied simulation network (anterior cingulate cortex, superior frontal gyrus, motor cortex, and inferior parietal lobule), an emotional processing network (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, and inferior frontal gyrus), and a subcortical parenting network (amygdala, hypothalamus, and mesolimbic pathway)6 (the Figure gives a detailed illustration of the paternal brain network).

Figure. Brain Network of Paternal Brain

After childbirth, a father’s brain shows increased activity in the human caregiving network. This system encompasses a mentalizing network, an embodied simulation network, an emotional processing network, and a subcortical parenting network (amygdala, hypothalamus, and mesolimbic pathway). These changes have been associated with greater activation in emotion processing networks in fathers toward their own infant interactions, compared with childless men.

Increased activations in the medial prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, insula, inferior frontal gyrus, and superior temporal sulcus were observed when fathers watched images or heard sounds from their infants compared with unfamiliar infants.7 Moreover, watching infant pictures, as opposed to adult images, was significantly associated with increased activity in the orbitofrontal cortex, with this activation being greater in fathers than in nonfathers.6 However, it is unclear whether these functional brain changes occur in the postpartum period or begin during pregnancy.

Most research has focused on paternal brain plasticity after postpartum caregiving experiences, comparing fathers and childless males to identify morphologic and functional differences.5 Although fathers do not experience the mother’s physiologic and hormonal changes associated with pregnancy, these studies neglected potential early paternal brain changes during pregnancy. Studies have shown decreased testosterone levels in expectant fathers during their partner’s pregnancy,8 and these hormonal differences have been shown to correlate with brain responses to infant stimuli after childbirth.5 Another study revealed correlations between gestational age and activation of the left inferior frontal gyrus and the amygdala in expectant fathers.2 Taken together, these findings suggest that hormonal dynamics may influence paternal brain plasticity during pregnancy, early before the first caregiving experience.

Steroid hormone signaling pathways, including those involving androgens, estrogens, and progestogens, may remodel the paternal brain during pregnancy. Higher oxytocin levels and lower testosterone levels have been associated with increased parenting behaviors and father-infant interactions.9 Furthermore, plasticity can be shaped by experiences associated with the onset of fatherhood, such as cohabitation with a pregnant partner.10 In an animal study, cohabitation with an unrelated female increased the expression of vasopressin messenger RNA in neural pathways mediating hippocampal regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system and decreased the expression of vasopressin peptide in the lateral septum and lateral habenular nucleus.10 These findings suggest that investigation into how and when such variability in paternal phenotypes emerges is needed.

Further research will also be crucial for understanding the brain mechanisms involved in paternal depression and anxiety during the perinatal period. Approximately 8% of fathers present with postpartum depression in the year after childbirth, but the neurobiological mechanisms involved in this are still unknown. The brain changes observed in fathers affect areas involved in emotional regulation, and this perinatal neuroplasticity could increase vulnerability to mental health conditions, weakening the ability to cope with stress factors.

Advancements in human neuroscience offer opportunities to investigate whether hormonal and experience-related factors shape the paternal and maternal brain differently during pregnancy as well as the implications for caregiving post partum. As with the maternal brain, longitudinal studies are needed to compare morphologic and functional changes in fathers’ brains during preconception, pregnancy, and the postpartum period. We urgently need to better understand the cerebral processes that affect the paternal brain.

Article Information

Corresponding Author: Hugo Bottemanne, MD, Institut du Cerveau, Paris Brain Institute, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, UMR 7225/UMRS 1127, INSERM, 47 Boulevard de l’Hôpital, 75013 Paris, France ([email protected]).

Published Online: November 13, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.3592

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Additional Contributions: We thank the Paris Brain Institute for supporting this study.

References

1.

Servin-Barthet C, Martínez-García M, Pretus C, et al. The transition to motherhood: linking hormones, brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2023;24(10):605-619. doi:10.1038/s41583-023-00733-6PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

2.

Diaz-Rojas F, Matsunaga M, Tanaka Y, et al. Development of the paternal brain in humans throughout pregnancy. J Cogn Neurosci. 2023;35(3):396-420. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_01953PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

3.

Paternina-Die M, Martínez-García M, Pretus C, et al. The paternal transition entails neuroanatomic adaptations that are associated with the father’s brain response to his infant cues. Cereb Cortex Commun. 2020;1(1):tgaa082. doi:10.1093/texcom/tgaa082PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

4.

Kim P, Rigo P, Mayes LC, Feldman R, Leckman JF, Swain JE. Neural plasticity in fathers of human infants. Soc Neurosci. 2014;9(5):522-535. doi:10.1080/17470919.2014.933713PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

5.

Abraham E, Hendler T, Shapira-Lichter I, Kanat-Maymon Y, Zagoory-Sharon O, Feldman R. Father’s brain is sensitive to childcare experiences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(27):9792-9797. doi:10.1073/pnas.1402569111PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

6.

Feldman R, Braun K, Champagne FA. The neural mechanisms and consequences of paternal caregiving. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2019;20(4):205-224. doi:10.1038/s41583-019-0124-6PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

7.

Abraham E, Hendler T, Zagoory-Sharon O, Feldman R. Interoception sensitivity in the parental brain during the first months of parenting modulates children’s somatic symptoms six years later. Int J Psychophysiol. 2019;136:39-48. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2018.02.001PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

8.

Saxbe DE, Edelstein RS, Lyden HM, Wardecker BM, Chopik WJ, Moors AC. Fathers’ decline in testosterone and synchrony with partner testosterone during pregnancy predicts greater postpartum relationship investment. Horm Behav. 2017;90:39-47. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2016.07.005PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

9.

Weisman O, Zagoory-Sharon O, Feldman R. Oxytocin administration, salivary testosterone, and father-infant social behavior. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;49:47-52. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.11.006PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

10.

Wang Z, Ferris CF, De Vries GJ. Role of septal vasopressin innervation in paternal behavior in prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(1):400-404. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.1.400PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref