The Psychology of Collective Victimhood

Part 2 of 3 in the series “The Victim Trap: How a Culture of Helplessness Took Hold”

When the mindset of victimhood spreads from individuals to entire groups, something powerful — and dangerous — begins to happen.

The sense of personal injury becomes a shared moral identity.

Suffering, once private, becomes political.

At first, this can bring solidarity and even healing. A wounded community finds its voice. People who once suffered in silence finally feel seen. But over time, the same force that unites can also divide. The story that once offered meaning starts to reshape how people see themselves, their nation, and even morality itself.

1. The Birth of a Moral Identity

When groups define themselves by what was done to them, they gain not only empathy but a sense of moral righteousness. The logic is simple — and intoxicating:

“We have suffered, therefore we are good. They have power, therefore they are bad.”

This moral binary simplifies a messy world. It provides clarity and belonging, offering the comfort of a single story where virtue and vice are clearly assigned. But it also freezes both sides into unchanging roles: one forever the victim, the other forever the oppressor.

These roles are psychologically powerful because they remove complexity — and with it, responsibility. Once a group becomes identified with innocence, it no longer needs to question its own motives. Its cause is automatically just.

Modern politics thrives on these fixed roles. They provide ready-made moral drama: heroes and villains, innocence and guilt. But like all drama, they require constant rehearsal to stay alive. Without conflict, the script falls apart.

2. The Emotional Rewards of Group Victimhood

Collective victimhood feels empowering at first. It transforms personal pain into a larger moral purpose. What was once chaos becomes coherence.

Being part of a group that has “suffered together” gives life meaning and creates unity. It offers protection from isolation. There’s comfort in saying, “We’re not crazy; we’ve been wronged.”

In social movements, this dynamic can quickly become a badge of belonging — a way to prove loyalty to the cause. Those who display the most outrage, or carry the most visible wounds, often gain the highest moral status.

Psychologists call this competitive victimhood: when groups begin to compete for recognition as the most wronged. The greater the suffering, the greater the virtue. But moral status can become addictive. Once a group learns that pain equals virtue, it begins to search for more pain — and when real injustices run out, it may start to manufacture offense to sustain its moral authority.

It’s a strange paradox: the more a group celebrates its wounds, the less it can afford to heal them.

3. Biases that Keep the Wound Open

Victim thinking doesn’t just change beliefs — it changes perception itself.

It amplifies cognitive biases that keep the wound raw and prevent healing.

Confirmation bias: Interpreting every disagreement or policy change as proof of oppression. The mind filters the world for evidence of persecution.

Attribution bias: Assuming malice rather than misunderstanding — reading intent where there may be none.

Availability bias: Because the media highlights what shocks and wounds, stories of cruelty stay vivid in our minds while quiet acts of goodwill fade from view. We remember every injustice, not because it’s most common, but because it’s most visible.

Moral typecasting: Once a group is labeled “the victim,” society struggles to see it as capable of harm — while the supposed “oppressor” becomes incapable of innocence.

This last bias deserves a closer look.

Social psychologists Kurt Gray and Daniel Wegner discovered that people intuitively divide the world into moral types: those who act (moral agents) and those who suffer (moral patients). Once someone is cast in one role, our minds tend to freeze them there.

That means when a group is seen as a victim, their actions are interpreted through a moral filter that excuses wrongdoing. Their pain becomes proof of virtue — and even when they cause harm, observers tend to explain it away as justified or defensive.

Conversely, those seen as oppressors carry a kind of permanent moral stain. Even their good deeds are reinterpreted as self-serving or manipulative.

The tragedy is that this bias prevents genuine empathy in both directions.

It denies accountability to those labeled as victims and compassion to those labeled as villains. In the end, everyone’s humanity gets flattened into a single moral role — and the cycle of grievance stays alive.

4. When Empathy Becomes a Weapon

Empathy is one of humanity’s most precious traits. But when victimhood becomes sacred, even empathy can be weaponized.

Claims of harm begin to override discussions of truth. Feelings become the final arbiter of morality. The question shifts from “Is this accurate?” to “Does this offend?”

The result is what might be called moral coercion: when guilt replaces persuasion and compassion becomes a tool of control. People censor themselves not because they’re wrong, but because they fear being seen as cruel.

You can see this dynamic almost anywhere today — in classrooms, offices, or online. A teacher hesitates to discuss a controversial historical event because one student might feel “unsafe.” A coworker swallows an honest disagreement during a diversity training, not because they’ve changed their mind, but because they dread being labeled insensitive. On social media, someone offers a mild counterpoint and is flooded with moral outrage until they apologize for the sin of questioning the narrative.

In each case, guilt or shame becomes a weapon. The emotional threat of being branded heartless silences discussion more effectively than any argument could. And so compassion, meant to connect us, begins to control us.

Ironically, the groups that appear most powerless often become the most influential, because they wield the moral authority of suffering. When pain becomes proof of virtue, disagreement starts to look like aggression.

It’s a subtle but devastating inversion: empathy, meant to heal division, becomes a tool that enforces it.

5. The Emotional Toll on the Group

Living inside a collective grievance feels purposeful, but it’s emotionally draining.

Righteous anger brings a surge of meaning — a sense of clarity and mission — but like any stimulant, it requires constant renewal.

A group addicted to outrage cannot rest. It needs a steady supply of offenses, real or imagined, to keep its story alive. When none appear, it begins to see insult in the ordinary and oppression in mere difference.

Without new conflict, the group’s identity weakens. This is why peace, paradoxically, can feel threatening to movements built on pain. Reconciliation robs them of their reason to exist.

The emotional cost is high: anxiety, exhaustion, paranoia, and isolation. The group’s members live in a permanent state of alert, bonded by fear rather than love.

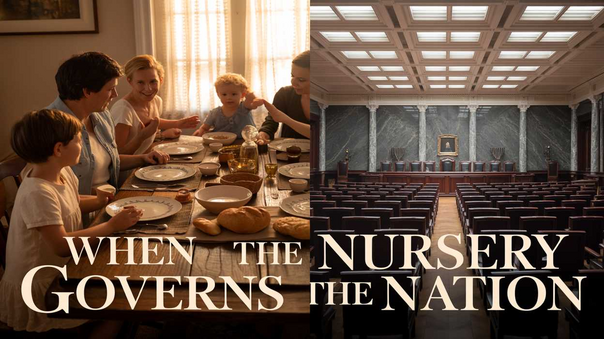

6. How Collective Victimhood Divides Society

The tragedy of group grievance is that it unites within but divides between.

Shared suffering bonds members of the in-group, but it hardens their hearts toward outsiders. Empathy becomes conditional — reserved only for those who share the same scar.

Once compassion is limited to “our people,” understanding dies. Dialogue collapses. Each side becomes trapped in its own moral narrative, convinced that it alone is righteous.

The cultural result is polarization — a society where everyone talks about justice while practicing vengeance, and where reconciliation feels like betrayal.

In such a climate, even kindness can be misinterpreted as manipulation. Every gesture is filtered through suspicion. Healing becomes nearly impossible because the wound has become the identity.

7. Toward a Healthier Collective Story

The way out is not to deny injustice but to transcend it.

Nations, communities, and movements can honor their suffering without making it their defining story.

That transformation begins with language.

Saying “We have suffered” keeps us anchored in the past.

Saying “We have endured” honors the same pain but adds strength.

The first sentence describes injury; the second describes resilience.

The difference seems small, but psychologically it’s immense — one keeps the wound open, the other begins to heal it.

Healthy cultures, like healthy people, move from grievance to growth. They tell stories not just of what was lost but of how they rose. They stop competing for sympathy and start competing for excellence.

Final Word

Victimhood once served a sacred purpose — to awaken empathy for the mistreated. It was meant to open our hearts, to remind us of our shared humanity and the moral duty to protect the vulnerable. When a culture witnesses suffering and responds with compassion, something profoundly good happens: justice grows, cruelty is restrained, and dignity is restored.

But somewhere along the way, that sacred purpose was replaced by something transactional. When victimhood becomes a currency, empathy turns into a market, and suffering becomes a brand.

You can see it in the way public life now rewards outrage and emotional display. A single personal story of harm, once told for healing, can now become a platform — drawing attention, sympathy, and sometimes even profit.

Organizations compete to showcase their pain as proof of virtue; individuals learn that expressing offense earns social status; corporations adopt slogans of solidarity not from conscience, but because compassion has become good marketing.

Imagine a town square where people once gathered to comfort the wounded. Over time, the square becomes a stage. The wounded are still there, but now they must keep their wounds visible, even open, because the crowd has learned to applaud pain more than recovery. The very empathy that was meant to heal now demands performance.

When compassion becomes currency, its value declines. What once flowed freely from the heart is now rationed, manipulated, and traded for attention or power.

The true mark of strength is not how loudly we proclaim our pain, but how gracefully we move beyond it. Real empathy — the kind that changes lives — begins when we stop spending suffering and start transforming it.

Our challenge now, as individuals and as a culture, is to remember that compassion and accountability must grow together — or both will die apart.

In the next and final part of this series, we’ll explore how modern institutions — academia, media, and politics — have learned to reward and monetize victimhood, and what that means for the future of honest conversation and human resilience.

Men Are Good.